Lessons Learned about Consequences & Incentives

Submitted by the AIHC Education Department

Introduction

The Office of Inspector General has released the new General Compliance Program Guidance or “GCPG” in late 2023. The GCPG is a reference guide for the health care compliance community and other health care stakeholders and provides information about relevant Federal laws, compliance program infrastructure, OIG resources, and other information useful to understanding health care compliance.

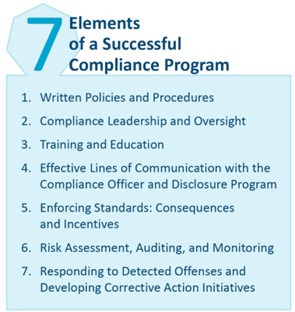

The GCPG standardized the seven Elements of a Successful Compliance Program, which differs slightly from the individual compliance guidance documents (CPGs) directed at various segments of the health care industry, such as hospitals, nursing homes, third-party billers, and durable medical equipment suppliers.

As health care organizations review and update current compliance programs to adapt from the CPG to the newer GCPG, remember to archive previous compliance documents according to effective dates. If you organization should come under scrutiny, you’ll need to produce how your program was implemented and how if functioned during the time of the potential violation.

One of the seven items, #5 is “Enforcing Standards: Consequences and Incentives.”

Within item #5 are directives from the OIG related to incentives. The OIG states the following:

“Entities also should develop appropriate incentives to encourage participation in the entity’s compliance program.”

“The compliance officer, Compliance Committee, and other entity leaders should thoughtfully consider the compliance performance or activities they would like to incentivize, both across the entity and within specific departments or positions. Excellent compliance performance or significant contributions to the compliance program could be the basis for additional compensation, significant recognition, or other, smaller forms of encouragement.”

The American Institute of Healthcare Compliance (AIHCTM) has released a 2024 Corporate Compliance Officer training program which is not only based on the new GCPC, but goes beyond to address quality, safety, HIPAA and other high-risk areas. One of the required reading assignments of this course is provided below to caution health care leaders when implementing incentives.

The Cobra Effect - A Study in Laws of Unintended Consequences

Written by Carl Byron, CCS, CHA, CIFHA, CMDP, CPC, CRAS, ICDCT-CM/PCS, OHCC

A long-term AIHC credentialed member and subject matter expert

EVERY decision or action we make carries unintended consequences. The “Cobra Effect” is a term coined for a solution that makes a current problem worse based on incentives, rewards and/or punishments exposing chinks in the planning. Perverse Incentives are nearly natural by-products, motivating unscrupulous individuals to game the system to make easy money or cut corners in regulations.

The “Cobra” - In the late 1800s-early 1900s when India was ruled by the British government, there was a problem with venomous cobras invading major cities. The British government decided to take action and offered citizens a bounty to redeem for dead cobras. While this was an effective short-term solution it eventually failed.

Indian citizens started breeding cobras for the cash reward. Cobra breeders killed the majority of the cobras and redeemed them for money while they continued to breed more cobras. The government eventually found out and stopped the financial incentives. The result? The cobra breeders released the snakes onto the streets since the snakes were no longer money makers - which made the cobra problem much worse. A variant of The Cobra Effect is known commonly as The Hanoi Rat Bounty.

When Hanoi, the capital of Vietnam, was under French colonial rule they discovered their villages had a major rat problem. So, the regime created a bounty program, similar to that of the British cobra bounty, that paid a reward for each rat killed. To get paid, people would provide a severed rat tail and get a little cash. Colonial officials, however, began noticing rats in Hanoi with no tails. The Vietnamese would capture rats, sever the tails, and then release them so they could reproduce more rats, thereby increasing the rat catchers' revenue.

The Cobra Effect is Alive and Well in Health Care

As you can imagine, the cobra effect is alive and well in health care. Whether leaders and policymakers are well intentioned or not health care is so complex, expensive and fraught with policies, laws, rules and regulations they make health care a very difficult maze to navigate. So much complexity in any arena will invite unforeseen consequences. Even well-meaning changes and upgrades to policies can make a previously compliant industry noncompliant.

Has the U.S. Learned from an Iconic Canadian History Lesson?

One of the earliest healthcare cases I know of occurred in Canada. The timeframe varies depending on the author; but it is generally agreed this took place from 1940 through at least 1960. It goes by the unassuming title of “The Duplessis Orphans”. According this article on the Canada’s Human Rights History page, this began in the mid 1940’s and continued into the 1960s when the Quebec government received subsidies from the Canadian federal government for building hospitals, but hardly anything to build orphanages.

- According to historians, government contributions worked out to be $1.25 a day for orphans, but $2.75 a day for psychiatric patients. So, to get more money from the government, the Catholic Church of Quebec frequently misdiagnosed orphaned children as mentally ill, affecting up to 20,000 people. This led to 80% of the misdiagnosed children reporting that they underwent a traumatic experience between the ages of 7 and 18, and over 50% said they underwent physical, mental, or sexual abuse.

More Recent History Lessons

An example likely familiar to many was in Forbes’ Aug 26, 2020, in an article entitled Beware Of The "Cobra Effect" In Business. The article states “An example of this was Wells Fargo in 2016. Wells Fargo wanted customers to use more of its products. It added incentives for its employees to sell more products and open more accounts to meet quotas. While the incentives did drive more sales and create more accounts, many of these new opportunities were not authorized by the customers. Instead of enhancing relationships with customers, the decision to offer these incentives influenced employees to act unethically, and it led to customers losing trust in Wells Fargo, as well as to the company simply losing customers.”

A Health Care History Example - Although slightly dated, being before the turbulence of the pandemic, an article appeared in the May 2018 Annals of the American Thoracic Society entitled Unintended Consequences of Quality-of-Care Measures demonstrates how the Cobra Effect is activated by certain moves made by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the single largest payer for health care in the United States.

To begin, the authors use Medicare patients who are diagnosed with aspiration pneumonia:

- “This study, one of the largest undertaken of aspiration pneumonia, confirms that patients with aspiration pneumonia are older, have more comorbidities, and are more likely to die than with other forms of pneumonia. Aside from its importance as an epidemiologic reference for aspiration pneumonia, this study found an association of hospital coding with quality metrics. Hospitals with the highest rates of coding aspiration pneumonia were much more likely to have low pneumonia mortality rates. Because aspiration pneumonia is excluded from Centers for Medical & Medicaid Services (CMS) pneumonia mortality scores, the implicit conclusion is that a hospital can improve its public rating by coding its oldest and sickest patients with pneumonia as having aspiration pneumonia. The reclassification of pneumonia into another diagnosis has been studied previously.”

- “When CMS scores are used to reward or punish hospitals, it takes little imagination to realize that a hospital could decide to improve its score by legitimately coding its sickest patients with pneumonia as having aspiration pneumonia. The authors found in this study that hospitals could improve their CMS scores by legitimately recoding patients with pneumonia into sepsis or respiratory failure. The study suggests that recoding patients does improve the scores.”

- The authors further state “More recently, we have witnessed Campbell’s law in medicine, where a Veterans Affairs hospital in Roseburg, Oregon, reportedly denied care to its sickest patients to improve its quality-of-care ratings. Doctors there were instructed to reclassify congestive heart failure as hypervolemia (an untracked diagnosis), and were instructed to admit veterans only as hospice patients, whose deaths would not be counted against the hospital. These interventions occurred as part of the unintended consequence of measuring and rewarding quality-of-care metrics.”

- “Hospitals and physicians want to improve the quality of their care. However, it is difficult to quantify care accurately. A high-volume referral hospital or a safety net hospital may have sicker patients and greater mortality in spite of providing better care. We attempt to adjust for this by characterizing and adjusting for these factors, albeit imperfectly. We report the measures of quality to an unsophisticated public, who may make financial decisions on the basis of these data. We penalize based on these imperfect scores, naturally leading to behaviors that optimize the score. Although it seems easy to look down on the hospital administrator or teachers who gamed the system, we should explore what characteristics of the system promote such behavior.”

The Cobra Effect and COVID

In light of the Public Health Emergency (PHE) ending in May, 2023, we find the Cobra effect very active during the PHE. In October 2020, Brigham Young University (BYU) issued the following warning: “Students who…have intentionally exposed themselves or others to [Covid-19] will be immediately suspended from the university and may be permanently dismissed." BYU apparently received credible information that some students were trying to become infected in order to score a bigger paycheck when donating plasma.

Healthy individuals are paid $50 per visit by a plasma donation center near the BYU campus. However, the same donation center offers $100 per visit for those with Covid-19 “convalescent plasma.” Like entrepreneurs seeking to capitalize on a niche market, some students may have seen Covid-19 as an opportunity to apply what they learned in Economics 101 about supply and demand.

After the pandemic had traveled its confusing and massively complex path for some time, studies started coming out showing how and in so many areas from politics to healthcare, the Cobra Effect savagely “bit” around the world. One of the biggest culprits? Some say the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Numerous articles have been published and, to summarize, the findings were that too many political leaders used the lockdowns as a knee jerk reaction to a rapidly spreading and unknown problem. They had never had to deal with anything like COVID before so perhaps the lockdowns were all they could think of. The Cobra Effect struck most places based on one policy: immediate lockdowns. And if anything (even if misreported) came to their attention about the disease gaining speed/victims, the politicians ordered more lockdowns.

Although it is not a formal study, an advisory was published by the State of Ohio on May 5, 2020. In the period of the pandemic to date, the State of Ohio went from a Fiscal Year (FY) state revenue surplus of over $200 million to a deficit of $776.9 million. The Governor had to balance the budget for the next FY (Ohio’s fiscal year ends June 30). Because of the abyss caused by the deficit, the Governor instituted the following reductions:

- March 23rd directive to freeze hiring, new contracts, pay increases, and promotions at all state agencies, boards, and commissions.

- Medicaid: Reduction of $210 million

- K12 Foundation Payment Reduction: $300 million

- Other Education Budget Line Items Reduced by $55 million

- Higher Education cut of $110 million

- All Other Agency budges reduced by $100 million

As an Ohio resident, I can attest the lockdowns were virtually immediate. Even when minimal return-to-work allowances appeared, the slow reopening policy backfired too. There were strict rules governing citizens outside their homes, such as the policy which continued the forced closure of day care centers and schools to remain closed even after parents were allowed to return to work.

Globally and with vastly differing economies and medical systems, the “cobra” struck without mercy, and for the same reason: hip-shoot decisions to lock the populations down far too rapidly. Not only did the lockdowns massively shift and reshape economies and people: the Disaster Risk Reduction study found another enormous problem was the resulting panic buying. People had precious little time but the politicians threatened all manner of punishment against “disobedient” citizens in most states.

Last, but by far not least, politicians in every sector of the globe were forced to contend with a global Cobra Effect result they are wrestling with to this day: civil disobedience. From defiance to open riots, citizens around the world started pushing back against what are increasingly being viewed as tyrannical moves by political institutions.

So, did the lockdowns actually make COVID cases worse? Maybe, maybe not. Did this affect healthcare? This remains to be seen, because as far as I can find the same entities who disregarded the civilian warning signs then are as willfully defiant now. I believe healthcare, as a profession, is safe. The media drew light on the suffering of health care workers during the height of the pandemic and because people still trust their doctors and health care professionals.

The Perverse Incentive or Cobra Effect?

Although the Cobra Effect and Perverse Incentives terms are loosely used together; they actually are different. A perverse incentive is an incentive that has an unintended and undesirable result that is contrary to the intentions of its designers. The cobra effect is the most direct kind of perverse incentive, typically because the incentive unintentionally rewards people for making the issue worse. Now, let’s take a closer look perverse incentives.

The Oxford Dictionary defines “perversely” as “in a way that shows a deliberate and obstinate desire to behave in an unreasonable or unacceptable manner; “in a manner contrary to what is expected or accepted.”

Perverse incentives arise from real or imagined problems or constraints from honest workers and intimate knowledge of gaming the system for the unscrupulous ones. When any organization’s people do not understand the environment, capabilities, technology and impact of external forces, they can and do make plans which are incomplete. If they do not involve the people who are the experts in the areas of concern the plan may already be doomed or “dead”.

Health Care Examples of Perverse Incentives

- Physician compensation arrangements incentivizing doctors to order diagnostic tests (result is increased revenue to the organization, increased provider wages but contributes to over utilization and health plans rate hikes). Also, because physicians are paid for doing things, they are being incentivized to provide services patients might not need.

- The hospital offers a monetary bonus to workforce members with perfect attendance, resulting in a dramatic reduction of absenteeism. This is what the company intended, so the incentive worked. Now, did the hospital set-aside the necessary bonus funds in the budget?

Cobra Effect with a decision tree extension - a self-initiated Perverse Incentive

This is a scenario most of us have experienced or at least can relate.

- You’re late leaving home for work. At the end of the street, you can take a right or left to get to work. You decide to take a right (which is a little faster than taking a left) and drive about 50 feet and pow – an accident happens just in front of you! Lucky you were not on time (it could have been you) – but now you look in the rearview mirror and see that if you had turned left instead, green lights as far as you can see with virtually no traffic.

- Walking into work, the boss catches you and states your presentation has been moved up to later this morning and must be done ASAP.

- Irritated, you finish the presentation and, in your hurry, decide to take your anger out on the project, making it sound unnecessarily aggressive.

- You present later that morning and at least some of the wording irritates the audience. So instead of showing your superiors you have a comprehensive plan with considered solutions, you have now just decreased their confidence in you, and they tell you so.

- Now you are into damage control and rebuilding your image.

Decisions we make are based on any number of variables (depending on circumstances, knowledge and capabilities): but in the scenario above, we only have ourselves to blame. The presentation affected more people negatively than just you or your time. Was it you? Was it chance/fate? Where was the perverse part inserted?

Even without more detail we can say it at least began with being late for work (lack of morning time management) and the problem became compounded when the decision was made to take that right at the intersection. Then more poor decisions were made due to controlling your frustration and changing the approach on your presentation, resulting in more trouble.

Stuff happens – but what mitigating factors, if employed, could have produced a better outcome? Was this an automatic Cobra Effect scenario? Perhaps not. This gets into another gray area, mitigation.

We are already late for work and know it: you still take the right, because it has proven to be faster in the past. The accident still happens. Now what?

- Call Your Boss - tell s/he you are at the scene of an accident.

- Get ahead of any impending situation by asking if there is anything pressing.

- Then you are informed that your presentation is moved up to that morning.

- Ask if there have been any changes, updates or news you need to be aware of.

- Use your cell to Email or call others in your immediate circle so they know you are stuck on the road.

- As soon as you arrive, seek out your boss and let s/he know you arrived.

Now for that presentation. Only the boss knew the presentation was moved. Pause, collect your thoughts and knowing most of the presentation was done already, modify your approach to meet the tight deadline and present it with passion. The day may not have gotten easier but it certainly got BETTER: and in the midst of it all, was a successful day. Your boss will notice your resilience.

This scenario is so minimal it could pass as just another day in the life of: but it shows the results of small decisions and how one failure can snowball into several or many depending on the methodology used to solve it.

Do any of these effects absolutely require a bad actor? No. With getting to work, the problem was we were late: the solution not only made us later; it had a downstream effect of making a poor presentation choice that to this point we were pretty well prepared for. There may be any number of variables that must be considered and discussed but there are even “sub-variables” which can still take the human element out and produce greater negative outcomes even when the designers of the plan or incentive have only best interests at heart.

Where Do we Go from Here?

Avoid the Fire! Ready, Aim syndrome

If dedicated workers possessing expertise in his/her field are left out of the drafting phase but are given a plan with orders to just “make it happen”, the executors of the plan may, even though they have the best interests of the organization at heart, feel forced to cut corners or disregard some issues in order to be compliant with the plan or policy forced on them. I call this the Fire! Ready, Aim syndrome.

The workers are forced onto a known undesirable track but their superiors will not hear counter arguments. These workers rather than implement the plan fully (compliant), implement the plan arbitrarily (perversely). This plan, whatever it was set up the perverse incentives by not looking at critical elements to ensure compliance. The workers were forced to perversely execute the plan.

The unethical workers are far worse and often cause far more disruption and trouble that are longer lasting and openly invite criminal investigations and prosecutions rather than corrective actions. Although in this scenario the perverse incentive is prewritten in the plan (due to the organizers’ omissions) the perverse incentive is immediately pursued. A workable, compliant result is not even considered.

Reversing or Mitigating the Cobra Effect

Because medical organizations vary so much by size, specialty, state they’re located, and a seeming maze of internal and external policies and personnel we will only cover general but effective ideas. First, in the assumption right now, the Cobra Effect has happened.

First, we need to look at exactly what happened. I am a Certified Internal Healthcare Fraud Auditor (CIFHA). If you have such training or experience, I recommend taking an investigative approach. For the sake of brevity, here are a few questions which can help you start your investigation, such as:

- Were laws broken?

- If so, what are the corrective measures (self-reporting) and potential consequences?

- Was the effect found by an external reviewer or auditor or through an internal whistleblower?

- Who exactly was responsible for launching the perverse incentive that went so wrong?

- Were providers/staff/employees affected?

- Who was involved in both the drawing and execution (Something went big-time wrong and we’ll need to ferret out the details.)

Next you must evaluate the outcome from the initial response to your questions and develop new questions – but you must ask the right questions. If you don’t, every answer will be wrong, and the unknowns become high risk and increasingly dangerous.

Great auditors know this and live by it. So, we must ask not only the right questions: but as many as possible so the outcome will be positive.

Although I haven’t seen the term for a while, you need to use deductive reasoning, meaning we have a known result and must rapidly work backwards to find the root cause(s). If possible, the best starting point is building an investigative element (or team) of people who understand the issue and know what was meant to be accomplished. Although the Cobra Effect typically involves bad actors, this is not absolute: well-intentioned employees who misunderstood or were put under pressure of some form could have made errors affecting the outcome. Any combination of missteps could cause a failure.

You need people dedicated to mission accomplishment who are accurate and effective investigators: and who have your organization’s health and best interests at heart. This team will gather all information and sift through it to determine the causes and produce either an alternate incentive to gain the same ground, or remove the incentive completely.

Add a Fishbone

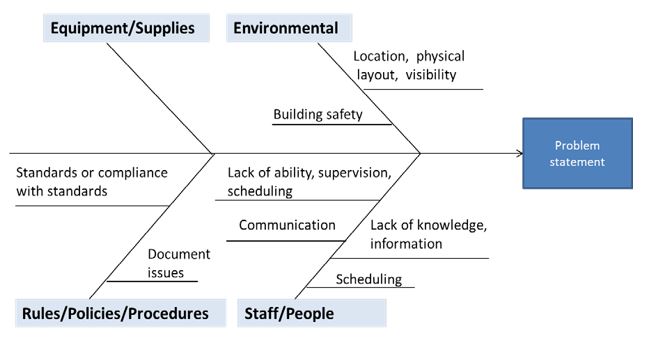

A very effective tool is the fishbone diagram. Both the American Society for Quality (ASQ) and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recognize this tool’s usefulness in root cause analysis (RCA). To determine shortfalls, omissions or bad actors, your team will need to produce a detailed root cause analysis.

The fishbone allows addition and insertion of critical elements, in this case as the investigation progresses; and it also allows for manipulation of the fish’s segments to better account for where in a process something occurred, and who was responsible for that segment. A great example is below, from the Minnesota Department of Health

Requirements for construction:

1. Problem Statement. Define a clear problem statement on which all team members agree. Be specific about how and when the problem occurs when a conclusion is reached and agreed upon.

2. Categorize major elements of the policy or incentive. There is no limit to how many of these “fish ribs” you can use. Use as many as will definitively detail the problem statement.

3. Brainstorm and build a comprehensive rib cage of Contributing Factors. *NOTE: This is a critical part of the investigation. Investigators must be (1) Unanswerable to the parties who built and sent the policy/incentive into the field. The investigators, like auditors must have the ability to interview individuals at any level and be unaffected by their motivations and safe from accusations or retaliation. Second, investigators must also be able to instill a sense of confidentiality and anonymity in the interviewees: their job is to determine and organize all the facts- not render judgment.

4. Be the detective. From the moment you begin ask why, who, where, when, what. With the Cobra Effect the central question (which should be repeated by the team constantly), is WHY. For example:

- Why was this overtime pay bonus started? Answer: Productivity stalled

- Why has productivity stalled? Answer: Outdated skills/brand new programs were put in our equipment

- Why were the skills outdated? Why did the new programs go live without proper training? Answer: This department suffered significant budget cuts and funds have not been increased or replaced. There has been no training on the new programs

- With the budget cuts last year the few people who knew the new programs were downsized.

- New hires did not fill the void and in X number of cases the few new transferees from department Y were not the right people for the job

5. The ribs can have “offshoots” or extensions. There is no limit to the number of ribs used to come to the conclusion. Just continually reevaluate to make certain of the conclusion(s)

6. Causes will expose themselves. Analyze them for repeat offenders which appear consistently not only within categories but between categories.

Avoid the recurring problem of “hyper-compartmentalization”

Many times, a plan will be incompletely drawn up, finalized and thrown into the field without some of the most important people’s input who will be involved in making the plan work: and many times, even those who are responsible for executing the plan get left out.

Employees, sections, departments and even executives do not speak to each other, or are guarded when they do due to being “territorial”. Important people in the manufacturing and execution of the plan go uninformed and only become aware of it when the “final” plan is sent with orders to execute it.

When the report is finalized, the investigating team must meet with all individuals responsible for bringing the policy or incentive to life: but caution must be taken to detail specifics and not pass blame or accusations.

More than likely some aspect involves a breach of compliance so compliance representatives must attend.

Depending on the monetary impact, people from finance may also be required, along with outside experts who can be objective and analyze your findings.

Who else must attend these debriefings should be delegated to the investigation team lead. If the investigation was conducted properly, the lead will have more precise details where the cracks in the plan occurred. Last, there must be someone neutral, and with enough authority to make the final decision and give the order how to proceed without contradiction or argument. If the Cobra Effect was damaging enough this might need to be done by your legal folks.

Mitigation

The investigative executive report details the problems, who was involved and specific findings: mitigation is taking the information from the meetings and either reworking the plan correctly or finding a way to withdraw it without causing further problems. This can be the same meeting as the debriefing: but it must include every party responsible for the plan, policy or incentive from start to finish. An additional party here might be someone who routinely does risk assessments for your organization. The plan failed once: if you plan to go through with it after one costly failure someone needs to evaluate the risks involved in trying again. Someone or even a small team must also be involved as monitors; watching, monitoring, measuring and evaluating each step or series of steps to ensure the failures that occurred before are avoided and thought through.

Last, if there were bad actors involved there must be a means to deal with them immediately and Human Resource experts should be involved. Again, neutrality of investigators is key. Plans must already be in place to deal with them immediately, conclusively and without regard to possible alliances or relationships.

Before the Cobra Strikes

Every action we take carries unintended consequences. Thus far we’ve taken a look at dealing with the Cobra Effect after it has occurred. Now let’s focus on preventing it.

Whereas before you were Sherlock Holmes and worked using deductive reasoning, now you need to use inductive reasoning and realize there will be unintended consequences. The outcome is unknown. Someone has determined this incentive, policy or plan must go forward. Now what? How can you plan for the unknown?

Consider utilizing a reverse fishbone diagram. Rather than the head of the fish being the problem, make the head of the fish the desired outcome. Then draw the spine to the tail and determine who will comprise the ribs. This is an unbeatable way to get input from important elements in the process and will involve parties who typically get left out of decisions. You can even let the different parts make their own diagram with processes: what we can do to facilitate the successful launch of plan at each level. They know best: listen and keep them involved.

Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) is an approach offered in the AIHC Certified Healthcare Auditor course. It is a structured approach to discovering potential failures that may exist within the design of a product or process. Failure modes are the ways in which a process can fail. Effects are the ways that these failures can lead to waste, defects or harmful outcomes.

Another term relevant in healthcare, and particularly to avoiding the Cobra Effect, is the Game Theory, or Gaming Theory. A great simplified definition is given by Brittanica and was updated June 2023 in the article game theory mathematics: “game theory, branch of applied mathematics that provides tools for analyzing situations in which parties, called players, make decisions that are interdependent. This interdependence causes each player to consider the other player’s possible decisions, or strategies, in formulating strategy. A solution to a game describes the optimal decisions of the players, who may have similar, opposed, or mixed interests, and the outcomes that may result from these decisions.”

The importance of using this to prevent the Cobra Effect can hardly be understated. Every party affected by the incentive will have their own view of it: their own expertise: their own loyalties and motivations. Depending on the extent of the incentive/plan/policy these parties may have (in fact or assumed), conflicting goals and motivations.

When I first studied Game Theory, a lot of experts stated Game Theory existed kind of in a vacuum; with parties competing based on, basically, selfish motivations. This has since been proven inaccurate, and rather than motivations many people are driven by rules.

- For example, rather than saying IT only looks out for itself, we now realize IT is an expertise: and based on their regular work, knowledge and experiences they approach objectives from a more technical aspect.

- Same with finance: rather than self-serving they tend to approach a goal with initial costs, what the outcome can make money-wise, how much it will cost to maintain, etc. Each segment in the plan lives under rules and constraints: so, in this vein using the term “game” is correct even if the fallout is potentially catastrophic or criminal.

So hopefully when you begin this process integrating Game Theory into your processes, you can see the value all parties bring to make the plan successful. And do not order: ASK. Brainstorm. Make every person and every idea count. In my experience healthcare employees tend to be closer to the military: they are proud of their work, they know their jobs and they see a greater purpose in the work they do and they recognize rank: Administration, Providers-Surgeons and Staff. Use this. Invite people with conflicting goals and abilities. Make certain the lead(s) listen. You may discover competing or conflicting goals may be traced back to conflicting abilities or even non-integrating technology that prevents a certain part of the plan from progressing. If there are competing motivations they can be addressed immediately. Potential bad actors can also be ferreted out at this stage. You may also, through this trust, get people to inform you in advance who the bad actors potentially are.

Realize employees recognize the rank structure. This can dovetail into Game Theory by integrating each stratum, and letting them draw up parts of the plan that directly involve them and their expertise. In over 30 years of working with providers and surgeons I know they’re known as fiercely independent and incisive and they think rapidly on their feet. But they’re also loyal and would far rather have input early, and be asked for their input, than be blindsided by an order to do something they never anticipated.

Building Trust Takes Leadership

Long before worrying about the Cobra Effect, healthcare organizations must build a cohesive people system based on individual value, trust and realization of a common mission. Then, when time comes for execution, no one is surprised; they all agreed to the plan and their part in it, and they realize there will be oversight to ensure the processes and outcome agreed on materialize. The executive section may determine what the need is: but the actual blueprints and construction should occur at the other levels.

Note how I don’t say “know your systems”; or “you’ll need massive data” or something similar. Many people are great with data but it either gets incorrectly manipulated or causes cracks between people. This is a common problem with reporters and sportscasters: they either have more data than experience or they lean heavily on data rather than experience. Data initiates nothing: it produces nothing: and it solves nothing. People do. Data is a tool but it cannot replace the people who do produce it. Data also foresees nothing: your best defense? Correct-people.

A revolutionary thinker was a quality engineer often credited with producing the meteoric rise of the Japanese auto industry after World War II: Dr. W. Edwards Deming. Deming was a reverse thinker (even by many of today’s processes) and believed people were the fundamental driver over data and, yes, incentives. If the Cobra Effect is a negative, unintended outcome, then to my mind Dr. Deming could be called “The Cobra Charmer”. One of his main focal points was why productivity and quality so often suffered unintended consequences. Sound familiar?

In an October 12, 2017 article over Dr. Deming I find the best characterization of him and his importance to Quality. The article appeared in the Quality Assurance Directorate (QAD) blog; QAD being part of the Royal Arsenal, United Kingdom: “Dr. W. Edwards Deming’s outlook on quality was simple but radical. He asserted that organizations that focused on improving quality would automatically reduce costs while those that focused on reducing cost would automatically reduce quality and actually increase costs as a result. He outlined his ideas simply in his theory of management, now known as The Deming Theory of Profound Knowledge.”

Finally, I leave you with a quote from the great General George S. Patton: “Never tell people how to do things. Tell them what to do and they will surprise you with their ingenuity.”

When an organization lives on and instills trust and realization of the value of different parts, people become above value. Conversing, sharing and involving them will reap unanticipated benefits. As General Patton saw cohesive teams can produce creative ways of problem solving and mission accomplishment. They might even find novel compliant ways of producing the desired results with less effort, or even superior results.

About the Author

Carl Byron is a full-time health care auditor for the Department of Defense. He is a certified coder with AAPC and AHIMA, and is certified by AIHC in Compliance (OHCC), Auditing (CHA), Investigations (CIFHA), Clinical Documentation Improvement (CMDP), Right of Access (CRAS) and as an ICD-10 instructor (ICDCT-CM/ICDCT/PCS). Carl volunteers on the AIHC Education Committee as a Subject Matter Expert.

Copyright © 2024 American Institute of Healthcare Compliance All Rights Reserved