Written by: Corliss Collins, BSHIM, RHIT, CRCR, CSM, CCA, CBCS, CPDC, Sheryn Honest, MBA, MLS, CHCO, CHA, CPC, Wendy Bartko, CPC, CEMC, CPMA, CPCO, CRC, CHA, CMDP, CIFHA

This article on Value-Based Care (VBC) addresses the importance of understanding the basics of data analytics to ensure C-Suite Executives have accurate information to make sound business decisions when engaging in new payment methodologies. We recommend reading Leadership in a Value-Based Care (VBC) Environment in addition to this article.

Why this Trend of Value-Based Care?

A 2022 report from the Commonwealth Fund U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2022: Accelerating Spending, Worsening Outcomes indicates that in 2021 the U.S. spent 17.8 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) on healthcare, which was almost two times the average of other high-income countries, while the health outcomes in the U.S. are worse than those of our peer nations across the world. Previous attempts to improve care and reduce costs has failed, thus, health care in the United States is shifting to a Value-Based Care model.

Over the past decades, the traditional method of reimbursing providers was in a fee-for-service (FFS) model. A provider would see a patient, document the visit, and select the procedure code(s) for the service(s). A claim would be generated and submitted to the payer. The payer would reimburse the provider according to their FFS contract, which typically had an allowable amount for each billable procedure code. Therefore, the provider would be reimbursed a fee for each service (CPT code) provided. As the cost of providing care grew, payers started instituting methods to curb expenses and how claims were paid. Payers started shifting to a shared-responsibility for expenses and expecting improved quality in the delivery and availability of care to their beneficiaries.

Medicare changed reimbursement methodology in the 1980s by introducing Relative Value Units (RVUs) and the RBRVS (Resource-Based Relative Value System) for physician reimbursement. Prior to this time, commercial carriers were already pushing HMOs (health maintenance organizations) and capitation contracts with physician networks or instituting "reasonable and customary charges" requiring physicians to collect data to negotiate reasonable contracts. Hospital reimbursement also changed. In 1983 Medicare shifted to the inpatient Prospective Payment System (PPS) and DRGs (Diagnostic Related Groups) and only paying a limited number of days to the hospital regardless of the actual length of stay. Medicare also encouraged improved hospital performance through the Hospital-Acquired Condition (HAC) Reduction Program, which is a Medicare value-based purchasing program that reduces payments to hospitals based on their performance on measures of hospital-acquired conditions (HACs). The HAC Reduction Program encourages hospitals to improve patients’ safety and implement best practices to reduce their rates of infections associated with health care. During this time (1980s - early 1990s) health spending increased at an accelerated which can be attributed to expensive new medical technologies and the curtailing of the ambitious HMO-promoting programs of the 1970s.

Those providers who were not prepared to manage the new reimbursement often resorted to “enhancing” revenue through “creative” means. As payers investigated insurance fraud, waste and abuse, increased oversight was implemented by creating Special Investigation Units (SIU) by many carriers and additional oversight by the Office of Inspector General (OIG) and stricter laws, such as the Antikickback Statutes, False Claims Act, Physician Self-Referral Law (Stark) with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) establishing a national Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control Program (HCFAC or the Program) under the joint direction of the Attorney General and the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

As more and more potential and real fraud, waste, and abuse was uncovered in the FFS arena, it was also discovered that patient outcomes were less than stellar. The poor quality of care, inefficiencies, and total cost to the U.S. healthcare system were exorbitant.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is using value-based programs to reward health care providers with incentive payments for the quality of care they provide to Medicare beneficiaries & support a three-part aim including:

- Better care for individuals

- Better health for populations

- Lower costs

2004 Risk Adjustment Implemented by CMS

Hierarchical condition category (HCC) coding is a risk-adjustment model originally designed to estimate future health care costs for patients. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) HCC model was initiated in 2004 and is becoming increasingly prevalent as the environment shifts to value-based payment models. Risk adjustment is a reimbursement method originally designed to estimate future health care costs using Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) coding which are to be submitted annually beginning January 1st.

Please note that accuracy of data collection is critical. Please reference the list of terms below under “Metrics”. Data quality, accuracy, completeness, consistency and predictive analytics all apply to HCC.

Value Based Programs are important in helping to move toward paying providers based on the quality rather than the quantity of care provided. The 5 original CMS Value based programs:

- End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program (ESRD QIP)

- Hospital Value Based Purchasing Program (HVBP)

- Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP)

- Value Modifier Program (Physician Value Based Modifier/PVBM)

- Hospital Acquired Conditions Reduction Program (HAC)

Two additional programs:

- Skilled Nursing Facility Value -Based Purchasing (SNF-VBP)

- Home Health Value Based Purchasing (HHVBP)

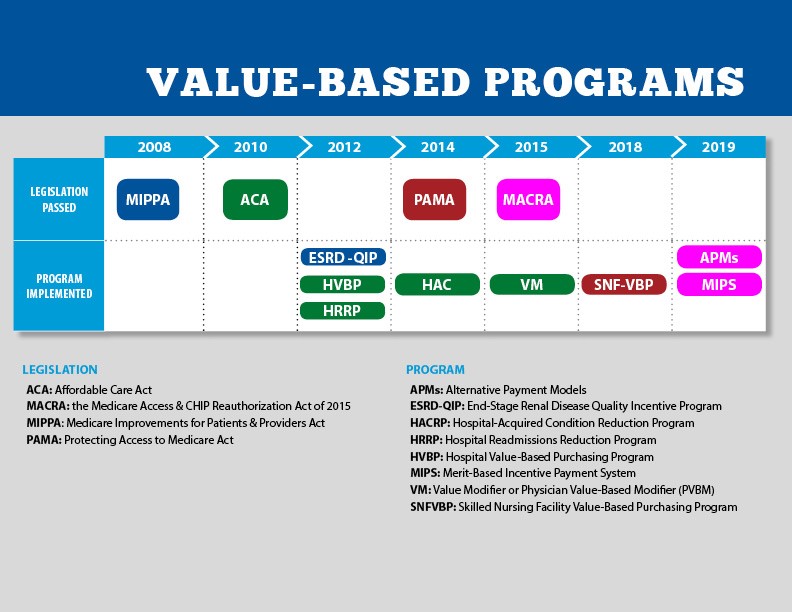

Going back to at least 2008, different legislation including MIPPA (Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act) was passed. These different Acts initiated the testing of alternate forms of delivering care and payment methodologies. The image below is the timeline from CMS.GOV regarding Medicare specific value-based programs and a more aggressive government initiative to institute reimbursement for Value-Based Care (VBC).

VBC is the current attempt to undo the perfect storm in healthcare. VBC is patient-focused and looks to increase the quality, coordination, and access to care, while reducing the cost of care. There are four types of prevalent VBC models:

- Pay for Performance can be a combination of FFS reimbursement plus additional incentives for providers/facilities to meet specified quality metrics. Overtime, metrics have been developed by many organizations including, the National Quality Forum (NQF), the Joint Commission, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ), and the American Medical Association (AMA).

- Bundled payments group together a service, procedure, hospital stay, or condition along with multiple service providers are needed to perform the service (e.g., hospital, outpatient provider group, specialty care, radiology, laboratory). A dollar amount is allocated for the service and any cost containing savings are distributed back to the service providers. These service providers are required to coordinate care amongst each other, in order to maximize cost containment. If the cost exceeds the allocated amount, then the services providers would be responsible for covering the exceeded cost.

- Shared Savings (e.g., ACO) combines quality care outcomes with reduced healthcare spending by having collaborative and coordinated care amongst the service providers. There is more financial risk for service providers participating in Share Savings programs, but there is also more financial incentive when quality and cost-efficiency are maximized.

- Capitation (e.g., MA/HMO) is typically used by Health Maintenance Organizations and Medicare Advantage Organizations. A per member per month (PMPM) reimbursement is established by the insurance company and the service provider has to manage all care within the PMPM payment received. The patient’s care is managed by a gatekeeper (aka Primary Care Provider (PCP)) who coordinates all care (ideally in an outpatient setting) amongst other in-network service providers.

- This is the riskiest model since there is both upside and downside risk that the gatekeeper is responsible for.

- Reimbursement can fluctuate based on the (good or poor) health of the patient. Diagnosis codes submitted to the payer determine reimbursement levels…the more ill the patient (with chronic disease(s)), the more the reimbursement allocated to the patient.

In all of these models, knowing how your business is running is key to managing outcomes. The main way of knowing how your business is running is through understanding your numbers. Having relevant, accurate, and timely data analytics is one of the most important keys to success in any healthcare organization.

Metrics

Data analytics metrics are used to assess the performance, effectiveness, and impact of data analytics processes, projects, and initiatives. These metrics help organizations understand how well they use data to make informed decisions. Testing the accuracy of the data your organization is collecting is critical. Inaccurate data could cause C-Suite Executives to lose confidence in your abilities, whether you are in-house working as part of the workforce in the finance department or a consultant.

Specific metrics may vary depending on the goals of the analytics project and the nature of the data being analyzed. Please see some of the most commonly used data analytics metrics below:

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are essential metrics that directly align with an organization's strategic goals. They can be financial, operational, or customer-focused. Examples include revenue growth, customer retention rate, and cost reduction.

Data Quality: Metrics related to data quality assess the accuracy, completeness, consistency, and reliability of the data being analyzed. Examples include data accuracy, data completeness, and data consistency.

Data Processing Time: This metric measures the time it takes to collect, clean, transform, and load (ETL) data before it can be used for analysis. Reducing data processing time can lead to more timely insights.

Data Accuracy: It quantifies how precise and error-free the data is. High data accuracy is crucial for making reliable decisions.

Data Completeness: This metric evaluates the proportion of data that is present compared to the total expected data. Incomplete data can lead to biased or unreliable results.

Data Consistency: Data consistency measures how well data is aligned and harmonized across different sources and systems. Inconsistent data can lead to discrepancies and confusion.

Data Volume: The amount of data being processed or stored. It can help determine storage and processing needs.

Data Velocity: This metric assesses how quickly data is generated, collected, and processed. It's particularly relevant for real-time or near-real-time analytics.

Data Variety: Data analytics often involve different data types (structured, unstructured, semi-structured). Measuring data variety helps ensure that diverse data sources are appropriately managed.

Data Latency: The time delay between data collection and its availability for analysis. Low-latency data is crucial for real-time analytics.

Data Retention Rate: Measures how long data is stored and maintained for future analysis. It's important for compliance and historical trend analysis.

Data Accessibility: This metric gauges how easily data can be accessed and utilized by analysts and decision-makers.

Data Security and Compliance: Metrics related to data security and compliance assess the protection of sensitive data and adherence to regulatory requirements, like GDPR or HIPAA.

Data Usage and Adoption: Measures how frequently and effectively data analytics tools and insights are used by the intended audience within the organization.

ROI (Return on Investment): Evaluates the value generated from data analytics initiatives compared to the resources and costs invested.

User Engagement and Satisfaction: Metrics related to user experience and satisfaction with data analytics tools and dashboards.

Model Accuracy and Performance: For machine learning and predictive analytics, these metrics assess how well models perform in making accurate predictions.

Data Visualization Effectiveness: Measures the clarity and usefulness of data visualizations in conveying insights.

Data Governance Metrics: These include metrics related to data cataloging, metadata management, and data stewardship practices.

Data-driven Decision-Making: Metrics that track how data analytics influences and improves organizational decision-making.

It's crucial to select and track the metrics that align with the specific objectives and context of your data analytics projects. Regularly reviewing and analyzing these metrics can help organizations make data-driven improvements and achieve better results.

Conclusion

We can count on payers continuing to shift the burden of cost to providers. And, it is expected that providers will continue to strive to provide quality and safe care at a reasonable cost. However, with rising inflation, sky-rocketing expenses for the latest technology and the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) integrated into our health care systems (which doesn’t come cheap), the ONLY way providers will financially survive a VBC environment is to negotiate appropriate, reasonable terms with payers based on accurate and reliable data.

This article is written by members of the AIHC Volunteer Education Committee. AIHC is a non-profit organization. We value our members, credentialed professionals and greatly appreciate the talents offered by our member volunteers!

Copyright © 2023 American Institute of Healthcare Compliance All Rights Reserved