Written by Joanne Byron, BS, LPN, CCA, CHA, CHCO, CHBS, CHCM, CIFHA, CMDP, OHCC, ICDCT-CM/PCS

Because healthcare organizations are heavily regulated and periodically audited or investigated, conducting internal audits is important to mitigate risk. Internal audits can be an integral part of your corporate compliance program and used as an effective management system, whether it is focused on quality, safety or any other business element. An internal audit, also known as a Management Audit, compares the implementation and effectiveness of the system against a standard as well as against its own internal criteria, as defined in policies, procedures and work instructions.

Introduction

Conducting business system audits is complex. The information provided in this article is not comprehensive and not intended as consulting or legal advice. The American Institute of Healthcare Compliance (AIHC) provides comprehensive training to certify healthcare auditors. You may consider enrolling in the online Auditing for Compliance course.

Undecided about becoming an auditor? Watch these recorded webinars posted to the AIHC YouTube channel, then decide.

What is a Business System Audit?

An audit is a process of comparing actions and/or results against defined criteria. Simply stated, an internal audit evaluates a health care organization’s management capability to determine answers to the following questions:

- Does a system exist?

- Is it implemented?

- Is it compliant to industry standards?

- Is it effective?

What is “defined criteria”?

Criteria is defined as the plural form of criterion, the standard by which something is judged or assessed.

- “Defined Criteria” are standards identified in advance and approved for use in a specific audit, generally set by government rules, regulations or government agencies, such as CMS or pre-approved by the governing board of your organization.

Are You Performing a First, Second or Third-Party Audit?

A first-party audit is performed within an organization to measure its strengths and weaknesses against its own procedures or methods and/or against external standards adopted by (voluntary) or imposed on (mandatory) the organization.

- A first-party audit is an internal audit conducted by auditors who are employed by the organization being audited but who have no vested interest in the audit results of the area being audited.

A second-party audit is performed by a legal or consulting firm or an individual retained to perform the audit for your organization for process improvement and risk management purposes.

A third-party audit is performed by an audit organization independent of the health care organization and is free of any conflict of interest. Independence of the audit organization is a key component of a third-party audit. Examples of these types of audits would be a Joint Commission, or CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) contractor audit.

- Third-party audits may result in certification, registration, recognition, an award, license approval, a citation, a fine, or a penalty issued by the third-party organization or an interested party.

Compliance is the Focus of All Audit Efforts

You are auditing for compliance. Compliance must be the focus of all your efforts. The auditor must first completely understand compliance standards for the purpose of auditing competently. Compliance standards must be written, staff trained, procedures implemented and followed, and monitoring performed to ensure the standards are being understood.

Fundamental Phases of an Internal Audit

Internal audits should not be limited to a business system or elements thereof, but should also incorporate Processes and Services where applicable. Whether there is one auditor or many, someone must lead the audit project. So, even if you are audit “team” of one, you must lead the audit process.

An auditor may specialize in different types of audits based on the audit purpose, such as to verify compliance, conformance, or performance. An auditor’s skills need to encompass the ability to provide advice and corrective actions when non-conformances are detected.

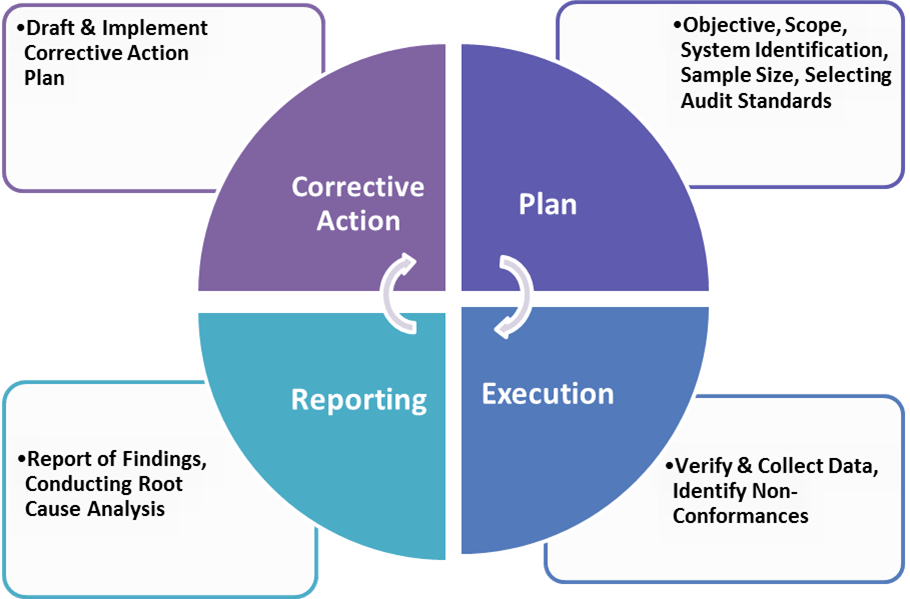

An internal business system audit has four fundamental phases – P E R C

- PLAN

- EXECUTE

- REPORT

- CORRECTIVE ACTION

The Planning Phase

Getting organized is crucial to a successful audit outcome. Never just jump in and begin auditing. The audit is significantly affected by poor planning and the opposite is just as true; great success can be realized when the audit is well planned. Before starting the audit, it is important to determine if there are any potential conflicts of interest where your determinations could be considered biased. Next, are you competent and considered a subject matter expert for this type of audit?

Next, realize that without preliminary information, planning, and understanding the criteria to audit against, your results are not likely to be on point! You may have to start the audit over completely if, as the Lead Auditor, you don’t understand the audit objectives from the start.

Drafting an audit plan includes writing down (at minimum) the following elements:

- Purpose of the audit;

- Objective (what is to be accomplished);

- Time frame & deadlines (start and completion dates);

- What items will be inspected;

- How many items will be inspected;

- How many auditors you will need; and

- Expertise required of the auditors for this project.

The seven items listed above become the introduction in your Report of Findings. Document this information sufficiently for ease of copying into your final report.

The Executing Phase

The best results come from building understanding and trust. Executing the audit is important and cannot be accomplished without cooperation from all parties involved in the project. You have only one chance to “launch” the project and do it well.

Develop a rapport with the auditee. Meeting to maintain communication is essential to develop trust throughout the audit process. Effective time management is important for several reasons:

- As a Lead Auditor, you have project deadlines to meet and likely have more than one project to oversee at a time. You need to work SMARTER, not harder!

- Remember, you are managing the expectations of your boss and the auditees. You have to collaborate and maintain transparency.

- Expect conflict – especially with difficult auditees which can “eat” up your time. Schedule conflict resolution time into the project.

- Your team must meet deadlines in order for you to complete the project. Therefore, it is important for your audit team to work effectively. They watch everything you do, so remember that you are their role model.

- Coach your staff. Be fair and impartial. Always be professional and expect your staff to always be professional. Part of being professional is respecting others time.

Utilize your leadership skills to influence the behavior of others to solicit cooperation. This all leads to efficiency and improved time management. Create checklists to stay on track.

Execution Activities

- Organize and document the Audit Standards and Criteria to be used to determine non-conformances

- Schedule and conduct the Opening Meeting

- Collect Data/Information

- Verify the information and measure compliance or non-conformances

- Record the non-conformities

Collecting Data/Information to Inspect

The purpose of the audit is to collect objective evidence regarding the effectiveness of a specific system, process, etc. In general, these audits should be a dynamic and practical tour through the business management system along a path prescribed by the auditor’s program and checklists which are aligned with the audit objective.

Collect relevant data! An auditor can gain much information by interviewing associates, observing activities or documenting evidence found in certain records. Interviews should not be limited to department heads, as everyone has a role to play in a business system.

Keep in mind that “hearsay” evidence is unacceptable to use as a basis for a non-conformance. You can, however, use the information to check if a discrepancy indeed exists. Without “hard” evidence, such as documented proof or an observation with your own eyes, you must give the auditee the benefit of the doubt.

Ask Questions – which is the best way to collect information to verify that your audit is heading in the right direction. Every auditor develops his or her own style and technique of questioning which evolves through experience and is fine-tuned on the basis of past successes and failures. The latter are bound to occur at some point, particularly when the auditor is new to his/her task and liable to errors both in commission and omission. Past experiences like this can be turned to advantages only if the auditor is willing to learn from them.

These are six words to remember which, when properly used, force a response:

- HOW?

- WHAT?

- WHY? WHY? WHY?

- WHEN?

- WHERE?

- WHO?

You may need to ask” why” as many times as necessary to get to the details needed for a thorough investigation or inspection of a process.

Verify your Observations

Auditors have to examine samples of documents, equipment, charts and so on to verify their observations. These samples constitute the framework for the audit with the sample size at the discretion of the auditor. When selecting samples for examination, politely insist on selecting the sample rather than asking the auditee to do so.

- The samples selected by the auditee are rarely random and more than likely will be the information that the auditee wishes you to see rather than what you might select.

- Remember that this is your audit and if a piece of information is missing you have the right to ask for it. However, it is crucial that you maintain a polite demeanor and remain objective in your audit activities.

Monitoring Audits

Monitoring follows the baseline audit. A monitoring system is usually initiated because of findings from the baseline audit. Monitoring is performed to assure continued compliance of the practice or facility after the initial or baseline audit. The objective is to measure process improvement. There may be multiple risks identified in the baseline audit resulting in various monitoring audits to be scheduled.

Monitoring should be conducted on a scheduled basis and should include such activities as:

- Reviewing utilization patterns

- Creating new comprehensive, focused audits to be performed

- Evaluating computerized reports (month-end and special reports)

- Assessing reimbursements (denials, EOBs)

Analysis and reporting after the audit are critical to set appropriate criteria for monitoring the process.

The Reporting Phase

The Lead Auditor must be prepared to statistically report audit findings and have the capability of understanding statistical results. Calculating error rates, accuracy ratios and breaking down findings into numeric values is an important component of the Report of Findings.

Analyze the data collected. In evaluating the results of an audit, be aware of the possibility of data acquisition errors. Using erroneous data can be worse than using no data at all.

- An error in data acquisition occurs whenever the data value obtained is not equal to the true or actual value that would have been obtained in a correct procedure.

- Such errors can occur in a number of ways. For example, an auditor might make a recording error, such as the transposition of a scored value of 25 on an audit checklist, to that of a value of 52 on an excel spreadsheet.

- Data should also be reviewed for unusually large or small values, called outliers, which are candidates for possible data errors.

Graphic illustrations such as charts, bar or pie graphs, etc., can be used to illustrate findings. Understanding how to use formulas is necessary to perform these functions. Accuracy and reliability of the reports will lend credibility to the entire audit endeavor and to the reputation of the Lead Auditor. Always write the report with your audience in mind. Choose charts, graphs, illustrations and data which can be understood by the reader. But before drafting the report, there are a few things to do:

- Verify the results of the non-conformances

- Be sure results are reproducible by other auditors on the team. Ensure the standards used are appropriate. Validate the error calculations and expand the sample size to ensure it is representative of the “universe”.

- Verbally share verified results with your immediate supervisor

- If you are an external auditor, performing an internal audit/review, verbally share results with the person retaining your services.

- An external auditor performing an internal audit/review should evaluate whether the project should be part of attorney-client privilege before sharing written results of any kind with the practice or provider.

- The audit reveals a potentially serious problem

- If “severe” or “disturbing” non-conformance is unveiled during an audit, initiate questions to gather important information.

- Does the non-conformance have a “trend” – is it the same error or type of error made over and over by the same provider or is it systemic? You may need to conduct a trend analysis.

- If you are unsure about the seriousness of the non-conformance, speak with your supervisor and suggest seeking consulting or legal advice prior to documenting a formal report.

When Documenting the Report of Findings

- Never make assumptions. All statements should be objective and backed up by evidence or “proof”. Be concise and report what you actually know, not what you “think” may be happening;

- Start the report with an overview so the reader understands who, what and why the report was generated;

- Provide an “executive summary” – a higher-level, bottom-line report of your findings. It is a summary of the results of the audit. Provide charts, graphs and other illustrations – “a picture is worth a thousand words”. Keep it short and concise;

- Provide the details of your findings which support what is in your executive summary;

- Use appropriate formulas and be sure your calculations are accurate; and remember -

- Do not exaggerate. Be honest when sharing your concerns. State only facts that can be supported by examples and supporting documentation in your audit findings and workpapers.

The Corrective Action Phase

Once the Report of Findings has been issued, someone needs to be responsible to follow through to ensure improvement takes place. This responsibility usually falls on the organization’s Compliance Officer. Corrective action is taken to address a system failure to ensure that it won't happen again, subsequent to a non-conformity raised during an audit.

To take corrective action, you must be clear about the who, what, when, where, and why. This typically involves conducting Root Cause Analysis.

Corrective action includes refunding overpayments revealed during the audit. This must be done according to payer guidelines and may involved self-disclosure to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) or the Office of Inspector General (OIG). Federal law requires entities repay any overpayments received from Medicare or a State Medicaid program within 60 days after identification.

Corrective Action Request Follows the Report of Findings

A Corrective Action Request should be issued to the auditee(s) after management has reviewed the audit report. Why?

- Because an audit uncovers areas where the system is not functioning in accordance to documented standards such as procedures and work instructions.

- Because an audit can identify the illness, but does not provide a cure. It must be followed by effective corrective action.

Corrective action activities involve:

- Identify the non-conformity (generally stated in the Report of Findings);

- Conduct Root Cause Analysis (to identify the underlying cause(s));

- Issue a Corrective Action Request with timetables and assigned responsible associates (assign accountability to have systems corrected, conduct training, etc.);

- Evaluate corrective measures taken (benchmark against previous performance, typically measuring against the Baseline Audit or the most current audit findings);

- Maintain accurate records to verify the corrective action has been completed [PDCA – addressed below].

- “Close-out” completed corrective action requests.

Management must assign follow-up activities with a designated champion.

- The objective of internal auditing is to determine if the business system is implemented and if it is effective.

- The objective of corrective action is to improve the business system.

Conclusion

When internal auditing and corrective actions do not function properly, the business system decays. Auditors need to be aware of this and take nonconformances in these areas very seriously. These two elements tell the whole story about a company’s understanding of and commitment to the quality system. The internal audit is best suited to verify effectiveness.

The task of an internal auditor is two-fold:

- Does the system comply with OIG Compliance or other Standards and Requirements (Joint Commission, HIPAA, etc.); and

- Is the system complete, relevant and consistently applied?

If internal audits are performed with these perspectives in mind, they can assess the effectiveness of processes, offer a constructive view of the business system and performance, and be an extremely valuable organizational tool.

About AIHC and the Author

American Institute of Healthcare Compliance (AIHCR) is a non-profit healthcare training organization and a licensing/certification partner with CMS. The author, Joanne Byron, shares her clinical, consulting, auditing and educational experience by serving as the Board Chair of the and overseeing the AIHC Volunteer Education Committee.

Copyright © 2024 American Institute of Healthcare Compliance All Rights Reserved