Written by: AIHC Blogger

This article provides educational information related to mitigating the risk of an unwarranted payer investigation. Only appeal claims when you have evidence and supporting documentation to substantiate your right to payment. This is the final article in a 3-part series on denials and appeals management. Read Part 1 entitled “Managing Denials Is Important to Good A/R Hygiene” posted March 22, 2022, and Part 2 entitled “Understanding How Payers Deny Claims.”

Audit Coding, Billing and Documentation for Accuracy

Insurance carriers and government contractors have the authority to review any claims at any time. Due to the huge volume of claims payers receive to process, deny and pay, they have implemented various methods to track providers to detect potential waste, fraud and/or abuse.

Providers may take documentation “short cuts” or feel overwhelmed with implementation of a new EMR (electronic medical record) system and clone or make documentation errors. It is important to detect any problematic areas prior to filing an appeal.

Lack of detailed supporting documentation submitted with an appeal can not only result in another denial, but also in “flagging” your practice as being high-risk on the spectrum of potential fraud and/or abuse. It can result in a situation where insurance opens an investigation or decides to initiate periodic audits on your claims and records. When you believe the payer is making the mistake, push back by exhausting all appeal rights allowed. If the payer, such as Medicare, performs an extrapolation, reducing each overpayment dollar through appeal can mean thousands less to pay back.

Utilize the information provided in the Part 2 article, such as ensuring the claim meets Medical Unlikely Edits, bundling, diagnosis and medical necessity guidelines. All modifiers should be appropriately appended and supported in the medical record. A great free modifier resource to share with you is the CMS Medicare Administrative Contractor (MAC) “WPS” learning center with on-demand training materials. Click here for the WPS modifier page (choose a region, the website will take you to the page).

Place of Service (POS) can be a “trigger” for an investigation. If the claim is coded POS 11 for the office, reimbursement can be higher than if the same service was performed at the hospital by the provider. Audit the POS to ensure this was coded correctly on the claim. A complete national POS code set and instructions are provided in CMS Internet-only Manual (IOM) Publication 100-04, Chapter 26, Section 10.5 at:

https://www.cms.gov/regulations-and-guidance/guidance/manuals/downloads/clm104c26pdf.pdf

Is the date of service (DOS) correct? When the medical record date doesn’t match the date filed on the claim, you may have a difficult time arguing an appeal. Payers always require documentation for the date of service filed (and paid) on the claim. When the DOS is incorrect, accept the denial. If you have not passed the timely filing deadline, re-file the claim with the correct DOS.

Audit to ensure your organization has no excluded individuals employed

An example of a case settled in 2022 is Windham Eye Group, an ophthalmology practice paying $192,000 for employing an excluded practice administrator. Please make sure your organization routinely screens employees to ensure none are on the OIG exclusions list. Prior to appealing a Medicare, Medicaid, TriCare or other Federal Program claim, you should verify that your organization is compliant in this area (click here).

Evidence of Medical Necessity

Medical necessity includes frequency, duration, previous conservative treatment (that failed) and other factors. However, it also includes documentation of a supporting diagnosis.

The diagnosis coding on the claim is one of the first items insurance will review to qualify the claim as being “medically necessary.” Once the diagnosis coding passes through the insurance company edits, additional edits will then be performed against medical necessity criteria.

Diagnosis codes are an important compliance aspect of reporting medical necessity on the claim. They are also a large contributing factor for potential fraud and abuse when documentation does not support the diagnoses reported. Auditing the diagnoses on the claim to documentation is a critical review step to determine whether the claim should be appealed.

- Diagnoses should be sequenced according to coding guidelines.

- Each line-item on the claim should be linked to the appropriate procedure code.

- Audit the code to ensure all characters are accurate.

- Each condition reported on the claim must be documented in the patient’s chart.

- Verify that the primary diagnosis is listed as “medically necessary” for the treatment provided.

Detect a Problem?

During the course of auditing or reviewing documents related to a denied claim, you may identify situations where further investigation is necessary. You may state it is simply a billing error. Errors made over and over in high volume or high dollar amounts will be interpreted as more than a simple billing mistake by payers.

- Make careful consideration before appealing denials found on an investigational probe.

Obtaining legal advice before proceeding with an appeal may be necessary under certain circumstances.

Carrier SIU Situations

Insurance carriers have departments called Special Investigation Units or “SIU” with trained professionals carefully reviewing allegations of suspected fraud and abuse.

When a probe or investigation is initiated by a payer in writing or in-person, it is likely the investigators have already been speaking with your billing staff and patients to gather information to establish a case against you.

Can the investigators “get it wrong”? They can, sometimes!

There are times when investigators believe the situation is intentional (fraud) when the problem actually is being caused by lack of internal controls, auditing and monitoring by the provider. This allows errors to continue for prolonged periods of time.

When your office receives the results of the SIU (carriers) probe, the letter will provide guidance regarding ability to appeal. If you are given the option to appeal, have evidence of a strong argument to support that these claims should be paid. If you can’t meet the deadline to appeal, request an extension to buy more time to audit and properly prepare your appeal argument.

If your organization has a Compliance Officer and/or Certified Healthcare Auditor, you may want to bring concerning situations to his/her attention. Never file an appeal when you believe documentation may be evidence of fraud or abuse. You may need assistance from someone more highly trained in this area to determine this. If in doubt, check it out.

When speaking with your provider, Compliance Officer, Auditor or an attorney, the “short” list of rules and regulations which apply to medical coding, documentation and billing are listed below.

- False Claims Act (FCA);

- Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS);

- Physician Self-Referral Law (Stark Law);

- Social Security Act; and

- United States Criminal Code.

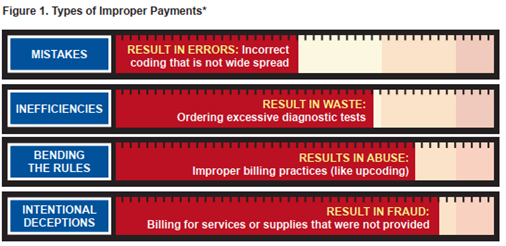

The difference between “fraud” and “abuse” depends on specific facts, circumstances, intent, and knowledge. Examples of abuse can include such things as:

- Billing for unnecessary medical services (lack of medical necessity);

- Charging excessively for services or supplies;

- Misusing codes on a claim, such as upcoding or unbundling codes;

According to the Medicare Integrity Program, activities which target various causes of improper payments are items such as those in the chart below.

The government's primary civil tool for addressing healthcare fraud is the False Claims Act (FCA).

- Most FCA cases are resolved through settlement agreements in which the government alleges fraudulent conduct and the settling parties do not admit liability.

- Based on the information it gathers in a FCA case, the Office of Inspector General (OIG) assesses the future trustworthiness of the settling parties (which can be individuals or entities) for purposes of deciding whether to exclude them from the Federal healthcare programs or take other action.

The OIG's efforts to curb fraud include:

- Conducting criminal, civil, and administrative investigations of fraud and misconduct related to HHS programs, operations and beneficiaries;

- Using state-of-the-art tools and technology in investigations and audits around the country;

- Imposing program exclusions and civil monetary penalties on health care providers because of criminal conduct such as fraud or other wrongdoing;

- Negotiating global settlements in cases arising under the civil False Claims Act, developing and monitoring corporate integrity agreements, and developing compliance program guidance.

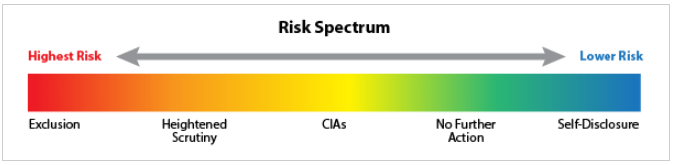

Because OIG's assessment of the risk posed by a FCA defendant may be relevant to various stakeholders, including patients, family members, and healthcare industry professionals, the OIG makes information public about where a FCA defendant falls on the risk spectrum.

The five risk categories on the spectrum are defined below:

Highest Risk: Exclusion

- Parties that OIG determines present the highest risk of fraud will be excluded from Federal healthcare programs to protect those programs and their beneficiaries. Excluded individuals and entities are listed in OIG's Exclusions Database.

High-Risk: Heightened Scrutiny

- Parties are in the High-Risk category because they pose a significant risk to Federal healthcare programs and beneficiaries. This is because, although OIG determined that these parties needed additional oversight, they refused to enter Corporate Integrity Agreements (CIAs) sufficient to protect Federal healthcare programs. Parties in the High-Risk category that reached settlements since on October 1, 2018, or later are listed here.

Medium risk: CIAs or Corporate Integrity Agreements

- Healthcare providers and other entities in the Medium Risk category have signed CIAs with OIG to settle investigations involving Federal healthcare programs. Under these agreements, parties promise to fulfill various obligations in exchange for continuing to participate in the programs.

Lower Risk: No Further Action

- The OIG sometimes concludes that parties present a relatively low risk to Federal healthcare programs. As a result, OIG is not seeking to exclude them from those programs or require a CIA. OIG's cases against these parties are closed without evaluating the effectiveness of any efforts the parties have made to ensure future compliance with Federal healthcare program requirements.

Low Risk: Self-Disclosure

- A party may disclose evidence of potential fraud related to Federal healthcare programs to OIG. The OIG believes that doing so in good faith and cooperating with OIG's review and resolution process generally demonstrates that the party has an effective compliance program. OIG works to resolve such cases faster, for lower settlement amounts, and with a release from potential exclusion with no CIA or other requirements. More information about OIG's self-disclosure protocol – click here.

This ends Part 3 for the denials and appeals article series. There is so much more to share with you, however, as you can see, filing an appeal involves various considerations and skill sets. Register, train and certify in Appeals Management - Online, On-Demand!